Background

Once again, I am writing about Statistics and Data Science as a follow-up to the annual Joint Statistical Meeting held in the beginning of August in Toronto. This Blog may be a lot more understandable if you have taken the time to read Blog 22A: Statistics and Data Science: The Two Cultures. Once again, I will omit (for obvious reasons) any mention of any individuals and stick to MY perceptions, interpretations, and perspectives on what some folks said to me or in various sessions at JSM. Like Blog 22A, this is a bit long, so pace yourself or make sure you have enough time to read it, preferably in one sitting.

In Blog 22A, I outlined the two cultures by using the following table, which undoubtedly simplifies presentation of various arguments, but also – as with any simplification – is not the whole story.

| Statistics | Data Science | |

| Data sources | Experimental Design | Observational data |

| Analysis approach | Modeling | Fitting data |

| Interpretation | Definitive conclusions | Possible insights |

In Blog 22A, I wrote the following sentence: “Speaking as a statistician, the biggest issue that I have seen over the years is when the data scientists live in “their” culture (observational data, exploratory analysis) but make the leap to the “our” culture and portray findings as definitive conclusions.”

I felt a bit uneasy about writing that sentence because the we/they dichotomy is troublesome to me, though I admit it is difficult for me to shake it in this arena. At JSM, a statistician I respect very much said something like, “There is no we/they. There is only us.” He further implored me to think more holistically and inclusively; to consider that we are all on the same team and we need diverse skill sets to maximize the value we might extract from data. He noted that we are all in the same boat. Either we are all data scientists or none of us are data scientists. Thus, the title of this Blog: Whose Boat Is It Anyway?

We also discussed the recurrent discussion that seems to be universal in this arena: “How do you define ‘Data Science’ or how do you define a ‘data scientist’.” I could spend a lot of time citing articles in the lay press, blog sites, books and technical literature that have taken a stab at this. In my Blog 3: What Might Be, I addressed this more directly and completely with some specifics and references, including a section devoted to What is Data Science? The short answer is that there is no consensus on what Data Science is or what a data scientist is or does. There is reasonable alignment around the notions of having computational skills, statistical/mathematical acumen, and subject matter expertise in whatever arena the data scientist is working (e.g., medicine, business, economics, social policy). Since the answers vary, I thought I would take a serious stab at my definition of what Data Science is and thereby what a data scientist is or does.

First and foremost, Data Science includes the word ‘science,’ and therefore it behooves us to understand or define what is meant by Science. Here are some formal definitions:

“the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation, experimentation, and the testing of theories against the evidence obtained.” (Oxford Languages)

“Science is a rigorous, systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about everything.” (Wikipedia)

I think of Science as being fundamentally about discovering/uncovering and describing true cause-and-effect relationships in the natural world. This includes a process of exploration and gradual refinement, similar to peeling back the layers of an onion – an onion that appears to have an infinite number of layers.

I have written in other places the following:

Mathematics is the science of discerning what is true. It is about theorem and proofs. It is yes/no, black/white. It lives on the set {0, 1}.

Statistics is the science of discerning what is likely to be true. It is inferential. It is probabilistic. It lives in the interval [0,1]. The fact that it lives anywhere in that interval makes it enormously more complex and ambiguous than mathematics.

Data Science is …?

Let’s look at some definitions.

“Data Science is about identifying those variables and metrics that might be better predictors of performance.” From Bill Schmarzo’s blog describing this quote from the book Moneyball. (https://www.kdnuggets.com/2017/02/schmarzo-variables-better-predictors.html))

“Data science is the study of data to extract meaningful insights for business. It is a multidisciplinary approach that combines principles and practices from the fields of mathematics, statistics, artificial intelligence, and computer engineering to analyze large amounts of data.” (https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/data-science/)

“Data science combines math and statistics, specialized programming, advanced analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning with specific subject matter expertise to uncover actionable insights hidden in an organization’s data.” (https://www.ibm.com/topics/data-science)

Some sources do not define “Data Science” but rather describe a “data scientist.”

“Data scientists examine which questions need answering and where to find the related data. They have business acumen and analytical skills as well as the ability to mine, clean, and present data.” (https://ischoolonline.berkeley.edu/data-science/what-is-data-science/)

I did this exercise several years ago and made a word cloud which you can see in Blog 3: What Might Be. As noted in Blog 3, these definitions tend to focus on business: “performance,” “actionable insights,” “business acumen,” “insights for business.” Observational data as the currency is implied: “large amounts of data,” “hidden in organization’s data,” “where to find related data.” Some sort of modeling is also implicit when reviewing these descriptions (and ultimately websites): “analytical skills,” “predictors,” “advanced analytics,” “machine learning,” “analyze large amounts of data.” The exploratory nature of the work also emerges from the definitions: “might be,” “uncover,” “mine,” “extract.” These notions lend credence to my previous Blog 22A: Statistics and Data Science: The Two Cultures. There is even reference to mathematics, statistics, and programming with one interpretation being that these fields are subsets of Data Science.

Who’s Boat Is It Anyway?

So, this brings us to the title question for this Blog. Is Data Science the field descriptor with statistics, mathematics, programming, and data management as subfields … or is Statistics the field descriptor with Data Science as a subfield?

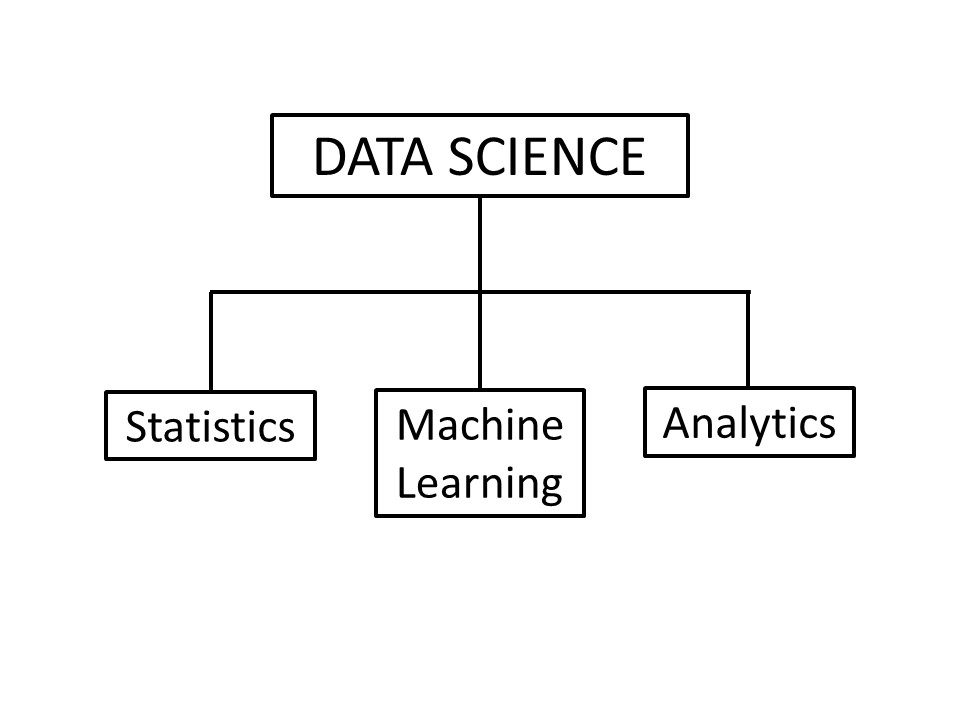

In a Harvard Business Review article, (https://hbr.org/2018/12/what-great-data-analysts-do-and-why-every-organization-needs-them), Cassie Kozyrkov describes the “’full-stack’ data scientist as having mastery of machine learning, statistics, and analytics” with analytics being associated with “data mining” or “business intelligence.” The author further states, “But what the uninitiated rarely grasp is that the three professions under the data science umbrella [my emphasis added] are completely different from one another.” The author equates statistics with rigor, machine learning with performance and analytics with speed as if to imply there are three “completely different” boats. She follows by an exhortation that businesses need more analysts, which I disputed in Blog 3. This harkens an image below.

Figure 1

Data Science as the Pinnacle Field

As in Blog 3, I think these descriptions can be debunked on several levels. First, the term “analytics” is way to broad to be meaningful as a label of a “profession.” Many scientific, business and government endeavors include many different kinds of people who “analyze” data. They can be formally trained statisticians using sophisticated hierarchical Bayesian models or product managers who have MS Excel skills. They can be formally trained epidemiologists analyzing complex health outcomes data or demographers using simple summary statistics. If you want to call them all analysts and throw them into the same boat, I guess you can do that, but what do you tell an aspiring analyst to study in school? Everything? Anything? Just know how to run SQL, SAS, R, or Python? I do not think this is what the author wanted or was implying. However, that author was focusing on the analyst as someone who does exploratory data analysis fast and is in their own boat (i.e., profession).

Furthermore, David Donoho in his excellent article 50 Years of Data Science (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10618600.2017.1384734 ) sheds light on the fallacy of some of these distinctions. He notes through plenty of examples that statisticians have long dealt with prediction, performance, big data, and exploratory data analysis (who in this area could forget John Tukey’s work on EDA or Edward Tufte’s work on visualization published decades ago). The American Statistical Association (founded in 1839 by the way) has 29 official Sections, including Sections on Computing, Statistical Graphics, Epidemiology, Marketing, Business & Economics, Defense & National Security, Sports, as well as perhaps more familiar Sections on Biopharmaceuticals, Quality and Productivity, and Bayesian Statistics – just to name a handful. There is even a Section dedicated to Statistics and Data Science!

In my view, the fallacy of Figure 1, as pointed out by Donoho, is that Machine Learning (prediction and performance) and Analytics (exploratory data analysis) are two manifestations of the field of Statistical Science.

So, does this harken an image with Statistical Science as the pinnacle field?

Figure 2

Statistical Science as the Pinnacle Field

Before trying to construct an answer to this vexing question, allow me to diverge to an analogy and then return to this conversation.

An Analogy

I think there is a useful analogy for clarifying this issue of Statistical Science/Data Science. That analogy is with the field of Medicine. Medicine has all sorts of generalists, specialists, etc. etc. And while some might see themselves as “superior” to others (CV surgeon vs general practitioner), they all see each as doctors. We/society all see them as doctors. All doctors have certain privileges – like prescribing medications – and certain responsibilities (in the US they are the liable person if something goes wrong with the patient). They are all in the same boat. They all have extensive medical training – some of it is common for all doctors, but then each doctor may pursue internships, a residency, and fellowships to hone their expertise in a particular area of Medicine. There is a system of accreditation, regulation, and continuing education that underpins all of this so that we patients may know who is or is not qualified to take care of our health or treat our ailments. Doctors are all in the same boat – albeit a large and diverse boat.

I can think more broadly of the “boat” of health care workers – nurses, physical therapists, physician assistants (not sure if other countries have that title, but they must have something akin to that role), dietitians, etc. They all take care of patients, and many have a shared knowledge of how to take care of patients. They have different levels of education, training and therefore skill at particular jobs.

It is worth noting that nurses can do things doctors cannot do or do not do very well.

It is worth noting that not all doctors have equal competence (hence the joke: Q: What do they call the person who got a C in med school? A: Doctor.)

For the patient, they are all on the same care team, and we hope and pray that they work together collaboratively.

But … we/society do not call nurses (or other health care providers) “doctor” for a reason. We do not allow nurse practitioners to perform surgery or other tasks that require a formal medical degree.

Let me go one step further. Suppose a person has a PhD in biology and has worked in an animal lab for years for a pharma company or government lab. That scientist has done surgery on animals routinely as part of their research. They have a deep knowledge of physiology and even medicine and pharmacology. Yet, society would never let that person open a medical practice or perform surgery on human patients. They are not in the “boat” with the doctors.

And it is not, “Either they are all doctors or none of them are doctors.” Just because I take care of a wound for my grandchild doesn’t mean I am in the boat with healthcare workers or doctors.

What’s the Boat?

So, this is what I see with data scientists. Some are trained in the science of data and analytics, and more and more are getting trained. But someone who has no training in variability, modeling, spurious correlation or respect for the scientific method and cause-and-effect should not be in our “boat.” Just because a person can run a computer algorithm from a canned package and slam data through it, doesn’t mean they are a data scientist (i.e., because I can take care of a cut with some soap, alcohol, and a Band-Aid doesn’t mean I am a healthcare worker).

I am NOT advocating that to be in the “boat” you have to have a PhD in Statistics. There are certainly statisticians who do some questionable work just like there are MDs who are not the best either (out of date, poorly trained, etc.). I do think the Data Science world (whatever that means) needs to be more clear about what training qualifies you to be in which boat (e.g., the doctor boat, the nurse boat, the healthcare worker boat). But right now, because access to data is easy, algorithms are plentiful and readily available, anyone with some computer skills can analyze data and produce “answers” with no accountability for such answers. At least in the Statistical Science world, there are well-established educational programs at the BS, MS and PhD levels, and many people have a reasonable understanding of what such degrees and titles mean, even if they only think of statisticians as doing hypothesis testing. Such structure may be emerging in the Data Science world, but if it is, it is far from mature.

So, here are some concluding thoughts.

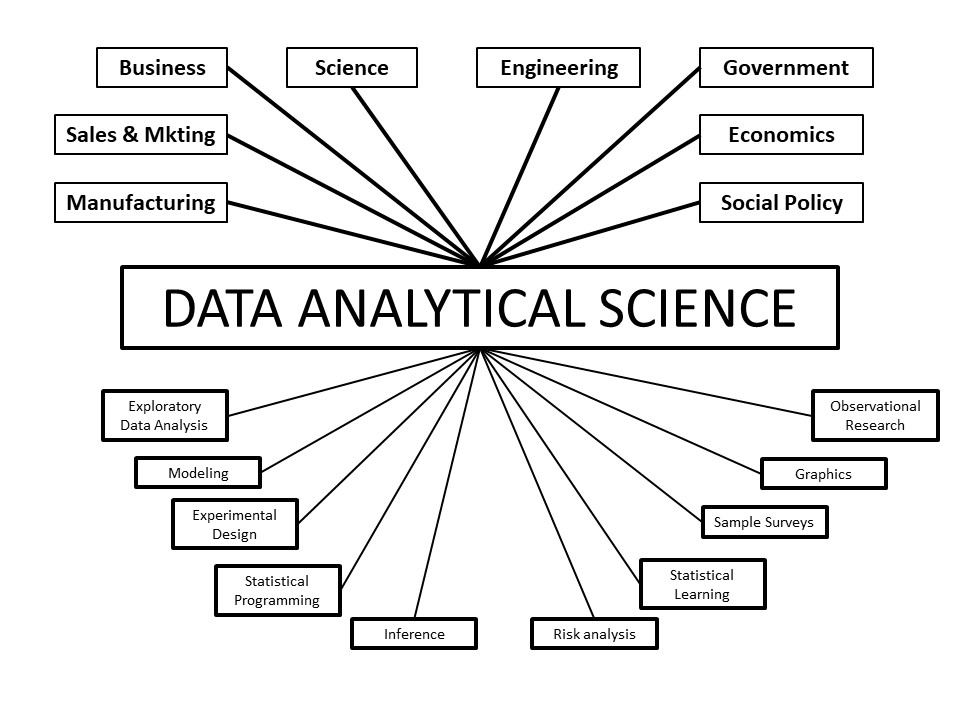

First, in some invited talks at conferences, I have noted that many professions that are deeply quantitative – statistics, economics, epidemiology, pharmacokinetics, etc. – are involved in the scientific pursuit of what the true/real cause-and-effect relationships are in Nature. All involve some level of exploratory analysis as a beginning point for uncovering possible relationships. All also strive to quantify their level of belief in a findings (at least the good and honest ones do), and recognize when a result is speculative, possible, or convincing. In those talks I have suggested that it is time for a new name for all of us as an umbrella for our work – Data Analytical Scientists. Why?

Data Analytical Sciences represents what we do. Many of the Data Scientists of today are actually not managing or manipulating or engineering data, but doing analysis (e.g., EDA, ML, prediction, etc.). So why not make that important and fundamental distinction clear?! I do not use simply Analytical Sciences because there is a whole cadre of laboratory sciences that goes by “analytics.” On a regular basis, I get emails or requests from laboratories or headhunters, especially when I was in charge of “Advanced Analytics” at Lilly. I do not want to confuse “us” (data analytical) with “them” (bioanalytical). They are not and should not be in our boat! Furthermore, it moves the debate out of the current boundaries, misunderstandings, useless competition, and disputes between Data Science and Statistical Science. As an inspirational speaker once said, “Don’t compete; CREATE!” So, I am creating a new name.

Thus, Data Analytical Sciences (DAS) is clear and perhaps is a step towards resolving some of the issues raised in this blog. It is a clear description of what we do – “data analysis” – though it does not explicitly include the notion of experimental design and survey sampling or other scientific aspects of collecting the right data. So be it. Neither did the word “Statistics.” [Note: When involved in a clinical trial design, I once had an MD ask me incredulously, “What’s Statistics have to do with clinical trial design?”] I insist that any moniker retains the word “Science,” and I think statisticians owe it to themselves to use the phrase statistical scientist more regularly. Maybe it should be the American Statistical Science Association (ASSA)! Maybe it should be the American Data Analytical Science Association (ADASA). In any case, I am comfortable saying, “I am a Data Analytical Scientist with a specialization in several areas of statistical science, particularly drug development.” Others can claim their specialty as they see fit; for example, “I am a Data Analytical Scientist with a specialization in quick and dirty exploratory data analysis of large datasets.”

Second, just as with the Medical profession, I prefer to consider one boat called Data Analytical Science, which includes many sub-fields of data analysis (including study design and interpretation of results – e.g. visualizations etc.). That boat is quite large and multi-faceted. It can be used in a vast array of endeavors – in fact, it is hard for me to imagine where Data Analytical Science cannot be applied. When giving a talk to senior management at my former company on the virtues of our company being more analytical and committed to using statistics across the enterprise, I had the following exchange.

1st Sr. VP: So, are you telling me that statistics/analytics applies to everything?”

Me: I believe so.

2nd Sr. VP: There must be some areas where statistics doesn’t really have a role to play.

Me: None come to mind for me right now.

2nd Sr. VP: Aah! What about love. Analyzing love.

Me: The websites like Match.com etc. use extensive statistical analysis to create matches, and they claim to have a better track record at creating lasting relationships for couples.

1st Sr. VP: Touché!

So, I would amend the schema in Figure 2 above with the following addition.

Figure 3

The New Boat for Sailing Forward

Third, many years ago (1980’s), I wrote, “If Mathematics is the language of science, then Statistics is the logic of science.” At that time, I was far less than fully informed about all the implications of this statement. Since then, I have learned that Francis Bacon wrote (ca 1250), “All science requires Mathematics.” And I have advanced my understanding of Statistical Science to be closely related to Epistemology, the branch of Philosophy dedicated to the theory of knowledge. I now see all Statistical Science pointing to the understanding of the true cause-and-effect relationships in Nature, that is, helping us establish what we know to a level of certainty that is allowable by how we know it (i.e., the context of the data and the methodology to analyze that data). That is the mission of Data Analytical Sciences as I see it.

Fourth, what is mostly Data Science today is a mixture of data analysis in one form or another and data management (now called data engineering in many circles). I think of the big boat of Data Analytical Science being related to some sort of summarization, analysis, distillation, modeling etc. of data. This includes experimental design to generate such data (controlled experiments, observational studies, sample surveys, etc.) as well as the statistical programming and other data manipulations for such analyses. I do not see data engineering (e.g., feature extraction from digital devices, data storage, merging/linking data or database, and other data preparation activities) as part of the Data Analytical Science boat. This is not to say that such activities are not important. They are extremely important! They just do not relate directly to the goal of Data Analytical Science – inferring what is likely to be true in Nature.

Fifth, as noted in Blog 22A, the problem arises when “data scientists” do statistical/analytical/modeling work and pass themselves off as experts in data analytics when they do not have the training/capability (i.e., the biologist who now thinks she is capable of performing surgery on humans). Alternately, I have encountered “data scientists” – even prominent or renowned ones – who have considerable skills with manipulation data and grinding it through algorithms but have little concern for Science, by which I am using my definition of science as discerning the true cause-and-effect relationships in Nature. I was told that on different occasions:

“I (data scientist) don’t care about cause and effect. That’s someone else’s problem.”

“We do not need causation anymore [and implicitly statistics]. With big data association is good enough.”

“I do not worry about multiplicity or spurious findings. The data will speak for themselves.”

Such “data scientists” simply reject some scientific principles. To some extent, I am fine with that kind of data scientist being in the boat, but I want them to acknowledge that they are doing EDA and nothing more. But, alas, my experience is they don’t; they think they are doing the real science (i.e., cause and effect) and they are unapologetic about it.

I do not know how to manage this.

I do not know how to resist without being called “the old guy who is out of touch.”

I do not know how to overcome the world’s hype and fascination with all things data science (or more recently AI or ChatGPT).

I agree with Cassie Kozyrkov’s statement in her HBR article: “Good analysts have unwavering respect for the one golden rule of their profession: do not come to conclusions beyond the data (and prevent your audience from doing it, too).” However, based on years of experience, this is VERY, VERY hard to do. In fact, other parts of the same HBR article suggest otherwise by describing the data analyst (i.e., one who does EDA very fast) as having a “mandate … to use data for inspiration” by being a good storyteller and using compelling visualizations. It seems quite difficult for the analyst to refrain from overselling or extrapolating beyond the data.

Sixth, in any emerging data science curriculum, statistical and scientific concepts should be taught, not just computing, analysis software, statistical/ML methods. Such concepts include experimental versus observational data, confounding, multiplicity, spurious correlation, overfitting, exploratory analysis versus prespecified analysis plans, randomization and experimental design, cause-and-effect. Honestly, I wish statistical curriculum taught more of these concepts. I certainly had to learn many of them on the job and over years of experience.

Perhaps most fundamentally, I think most data scientists are not trained the least in concepts like controlled experiments versus observational data – and most of the time they are dealing with observational data. In fact, as I have noted previously and in other blogs, data scientists grew out of the business world, and they are to the business world as epidemiologists are to the medical world: trying to extract meaningful information from observational data. Data scientists could learn a lot form epidemiologists, and certainly some have with the use of propensity scores, matching etc. Such efforts are in the minority from my perspective.

So, I would be happy to have a “we” world where we are all in the same boat, but I am afraid many (most?) data scientists reject the idea of being in our boat and in fact believe that our boat should be sunk and relegated to history. At least some I have met are of that mindset. They live in an exploratory world where anything goes and they do not want to be constrained by any rigor. That is fine if they were to describe themselves that way, but inevitably, their exploratory findings get conveyed as substantive. I am aware of data scientists that have no intention of writing anything down in any kind of analysis plan or pre-specified approach for analyzing the data. In fact, they reject this notion as bad science by limiting the creative/discovery process inherent in science!

Seventh, an equal problem is when statisticians are critical/skeptical of data scientists who bring legitimate capabilities to a “data analytic endeavor” but are dismissed because they do not have a statistical degree imprimatur. Statisticians can scoff at exploratory analysis and find all the reasons why any results should be viewed with skepticism, perhaps rightly from experience.

I do not know how to manage this. Stats has been “burned” by exploratory analysis and results that are oversold, and it is hard to regain trust.

I do not know how to encourage statisticians to get in the “boat” with data scientists, when statisticians (here I include myself) feel it is a step down from the rigor we try to bring to science.

I do not know how to overcome the world’s dismissive attitude to statisticians (as nerds, …).

I also find that data scientists seem to be much better attuned to visualization, and I mean effective use of color, shape and motion. I am reminded of the work of Hans Rosling and his historical demography plots. Statistical scientists can learn from this.

Conclusion

So, it is not “us” and “them,” but rather what “boat” are we talking about? Doctors can legitimately say “we” and “they” in some situations when referring to nurses. But in other situations, when discussing patient care or healthcare workers, the whole group is “us.” So it is with quantitatively skilled or analytically skilled professionals. There is the PhD statistician boat, and “we” can refer to clinicians as “they” in some circumstances, but in the context of a clinical development team, there is just “us.” Statisticians can legitimately refer to econometricians as “they” in some circumstances, but as “us” in others. I do not see this quite as a “we” and “they” issue but the context in which we refer to groups of people who have different skills and training.

At a cross-functional team level, what we have to do is respect the capabilities, knowledge, and skill that others bring to a group and focus less on whether we are all in the same boat and should be called the same name.

At a professional level, as a statistical scientist, I am happy to be in the same boat with data scientists – no we/they. But I have one condition … that it is the same boat. By that I mean one based on scientific principles and appropriate interpretation of findings/results. Not that we all have to agree on the interpretation of any finding/result. There is always room for scientific debate and differences of opinion. But a boat in which there is at least a common understanding of the quality of the data, the appropriateness of the analysis and some measure of the degree of certainty/reliability of any result.

ONWARD DATA ANALYTICAL SCIENCE!